2022-09-28: Using Web Archives in Disinformation Research

|

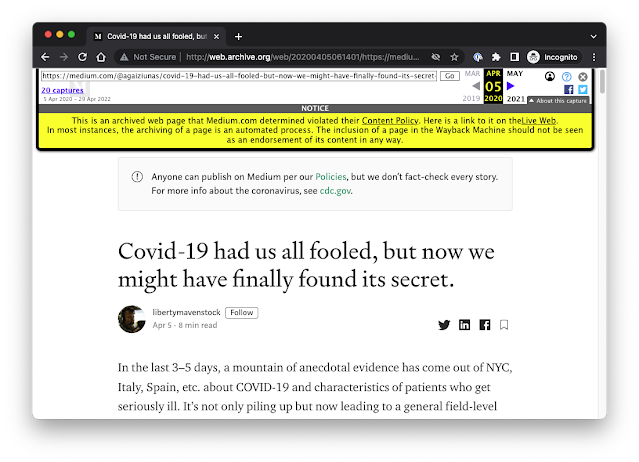

| Figure: Example of content label added by the Internet Archive |

Following on Lesley Frew's post looking at how journalists use web archives, I wanted to highlight some of the ways that web archives have been used to study disinformation over the past few years and to bring together some of the work that our Web Science and Digital Libraries (WS-DL) research group has done in this area. My interest in the intersection of web archives and disinformation has largely stemmed from developing a Disinformation lecture for our CS 432/532 Web Science course. Much of my reading was seeded by the work of Kate Starbird (starting with her ICWSM 2017 paper) and Amelia Acker (notably, her 2018 Data Craft report). My colleague Michael Nelson has built a graduate course, Web Archiving Forensics, around some of the topics discussed here.

|

| Figure: Mentions of "Wayback Machine" in news stories |

Webpages and social media posts can be modified or deleted or authors can be banned from the platform and their posts removed, so one of the first considerations is that we need web archives so that we can study the original materials later, even if they contain misinformation. Mark Graham, Director of the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine, has said, “It’s not about trying to archive the stuff that’s true, but archive the conversation. All of that is what people are experiencing.” In discussing their report on the 2020 US Election, "The Long Fuse: Misinformation and the 2020 Election", the Election Integrity Partnership noted that as they found notable posts, they archived them at the Internet Archive, so they would be able to go back later and actually write the report. This is becoming a common practice for journalists and investigative reporters, with citations and mentions of web archives, and especially the Wayback Machine, becoming more common in the press. There have been multiple tools and workflows developed to help journalists archive content, such as Bellingcat's auto-archiver and Raffaele Messuti's extension for the Brave browser that uses ArchiveWeb.page and Tor to allow for anonymous archiving of webpages.

In "Data Craft: The Manipulation of Social Media Metadata", Amelia Acker considers what web archives might hold that we haven't discovered yet, "Our web archives are now filled with examples of manipulation that were, at first, overlooked by platforms". Unfortunately, purveyors of disinformation also know about web archives. Some articles and posts that had been removed from their original platforms were still being shared via links to the Wayback Machine. However, this has prompted the Internet Archive to begin labeling some pieces of known disinformation.

Even pieces of the web that we might not consider important today, such as advertisements, may hold the key to understanding future disinformation campaigns, as suggested by Philip Howard in a New York Times editorial, "A Way to Detect the Next Russian Misinformation Campaign," writing, "Getting all ads, in real time, globally, into public archives is the next big step for strengthening democracy." We have long considered web advertisements to be important artifacts that should be archived and, with partners at Drexel University's College of Computing & Informatics, were recently awarded a grant from the IMLS for our project "Saving Ads: Assessing and Improving Web Archives' Holdings of Online Advertisements".

The most straightforward way to use web archives is to investigate changes to a webpage. Recently, US Senate candidate Blake Masters was in the news because his campaign removed references to his previous statements on abortion and the 2020 Election from his website. Reporters used the Wayback Machine to compare the text on his live webpage with that from previous versions. Masters is not the only candidate to make such changes heading into the 2022 US midterm general elections.

Related to this, web archives have also been used to validate claims about what someone has said or posted on social media. In 2018, my colleague Michael Nelson used multiple web archives, including the Library of Congress web archive, to verify screenshots of controversial content from MSNBC host Joy Ann Reid's former blog that had been posted on Twitter. Reid and her lawyers at one point claimed that the screenshots were fabricated or that the Internet Archive's versions of her blog had been hacked. In his post, "Why we need multiple web archives: the case of blog.reidreport.com", Nelson described the process of using the Memento Time Travel service and the Memgator tool developed at ODU to track down archived versions, or mementos, of Reid's blog in multiple web archives to corroborate the posted screenshots. |

| Figure: Memento Time Travel results for blog.reidreport.com on April 25, 2005 |

Final presentation @oducsreu presentations: @calebkbradford presenting "Did They Really Tweet That?" (mentor: @phonedude_mln). The project attempts to identify fabricated tweets through fact-checking and verification techniques. #oducsreu @WebSciDL @NirdsLab @oducs @ODUSCI @NSF pic.twitter.com/KejpypYQ2r

— Bhanuka Mahanama (@mahanama94) August 4, 2022

With many politicians and other public figures using social media for communication, archived social media posts have become important objects of study. Especially with former President Donald Trump's ban from Twitter, archives of his tweets have become important public records. This raises the issue of the quality of captures of social media in web archives. In our JCDL 2021 paper, "Replaying Archived Twitter: When your bird is broken, will it bring you down?", we highlighted some of the issues related to replaying tweets from web archives. This included problems caused for crawlers by Twitter forcing the use of their new user interface (UI) in June 2020, temporal violations upon replay with components of Twitter's new UI loading from different archived datetimes, and differences in how Twitter's fact check and violation labels replay in mementos between the old Twitter UI and the new Twitter UI. Together these issues with archiving and replaying tweets from web archives could make it difficult to verify what might have appeared on live Twitter, especially for accounts that have been banned.

In 2017, Justin Littman noticed that several US government Twitter accounts that were listed in the US Digital Registry had been suspended by Twitter. He used the Wayback Machine to discover that after the accounts had been deleted, their screen names had apparently been taken over by other users. Because the Wayback Machine indexes a webpage based on its URL and Twitter account URLs are based on screen names, mementos from both versions of the account would appear together in the Wayback Machine's list of mementos for the account. Littman even demonstrated this by briefly taking over the @USEmbassyRiyadh account and pushing a tweet with a picture of actor Wilford Brimley into the Internet Archive.

We have also explored how well (or not) Instagram has been archived, using Katy Perry's popular account as a proxy for all of Instagram. We found that although Katy Perry is the 20th most popular person on Instagram, only about 1/3 of her posts are archived in public web archives. Our interest in Instagram was piqued by the "The Tactics & Tropes of the Internet Research Agency" report that highlighted the IRA's heavy use of Instagram in their disinformation campaign. Instagram shut down their public API in 2018, limiting the ability of researchers to study the platform, and thus the platform is much less studied than either Facebook or Twitter. Another one of the projects from our 2022 NSF REU Site in Disinformation Detection and Analytics analyzed Instagram profile pages from the "Disinformation Dozen" and found that 96% of the mementos of those profile pages just redirected to the Instagram login page, so the profile page content was not actually captured. Many of these accounts have been banned from Instagram, so archived versions of their accounts are essential to study what they had been posting. This is a topic of ongoing research in our group.

Haley Bragg @haleybragg17 briefs her work on “How Well is Instagram Archived through the Years” during the @oducsreu 2022 program final presentations #oducsreu @WebSciDL @oducs @ODUSCI pic.twitter.com/A51Cco0WB2

— Bathsheba Farrow (@sheissheba) August 4, 2022

One of the issues with archiving social media is that traditional web archive crawlers, like the Internet Archive's Heritrix crawler, do not execute JavaScript while archiving a webpage, which may cause the archive to miss important resources loaded by JavaScript. Browser-based crawlers, which typically use headless browsers, do execute JavaScript and often can create more complete mementos, but they run much more slowly and are not suitable for web archiving at scale. The Internet Archive has developed the Brozzler browser-based crawler and uses it to archive certain webpages. The Webrecorder project has developed several tools leveraging browser-based crawlers, including ArchiveWeb.page and Browsertrix. Other tools for archiving social media include Social Feed Manager and twarc, which use APIs provided by the social media platforms to save social media posts and metadata. Unlike the crawlers mentioned above, they do not preserve the posts as they are displayed on the web.

The study of disinformation on social media often starts with a search for posts that contain certain keywords or hashtags. Kate Starbird's group has used this technique to study tweets about alternative narratives regarding the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill (e.g., posts containing the hashtag "#oilspill"), mass shooting events (e.g., posts containing both terms about shootings and conspiracy-related terms such as "false flag", "crisis actor", "staged", "hoax") and the UN response in Syria (e.g., posts containing the terms "white helmet" or "whitehelmet"). After gathering tweets with these terms that also contained URLs, they analyzed what domains were being linked to and often were able to identify groups of websites that formed an alternative media ecosystem. In one study, Starbird noted that they used the Wayback Machine to examine linked webpages that had changed or disappeared since the tweets were initially collected.

Often these initial investigations lead researchers to study individual accounts that are sharing disinformation, looking at who they are following, who is following them, whose posts they are sharing, who is sharing their posts. In "Data Craft: The Manipulation of Social Media Metadata", Amelia Acker studies disinformation by examining the social media metadata (follower counts, etc.) of particular accounts that are known to share disinformation. Acker considers case studies including politicians on Instagram, US government Twitter accounts, and IRA Facebook ads. The goal is to study the metadata of known manipulators to learn their techniques. Acker used web archives as a way of looking at social media in the past, including to examine the growth of an account's follower count. In "Acting the Part: Examining Information Operations Within #BlackLivesMatter Discourse", Starbird's group used the Wayback Machine to analyze tweets and profile pages of accounts that had been suspended by Twitter. A similar technique was used by Taylor Lorenz in her reporting on tweets by the then-suspended "Libs of TikTok" account. Her article in the Washington Post is filled with links to tweets archived by the Wayback Machine and is a great example of using web archives for evidence.

|

| Figure: Washington Post article with links to the Wayback Machine, annotation added by MCW |

This post highlights just a few examples of how web archives have been used to investigate possible disinformation, by examining how webpages have been changed, corroborating or refuting posted screenshots, studying archived social media posts, and investigating metadata and past behavior of particular social media accounts. One of our goals in studying web archives and how people use them is to be able to provide analysis and develop tools and techniques that can help promote the use of web archives and provide more confidence in them.

-Michele

Comments

Post a Comment